Lucia

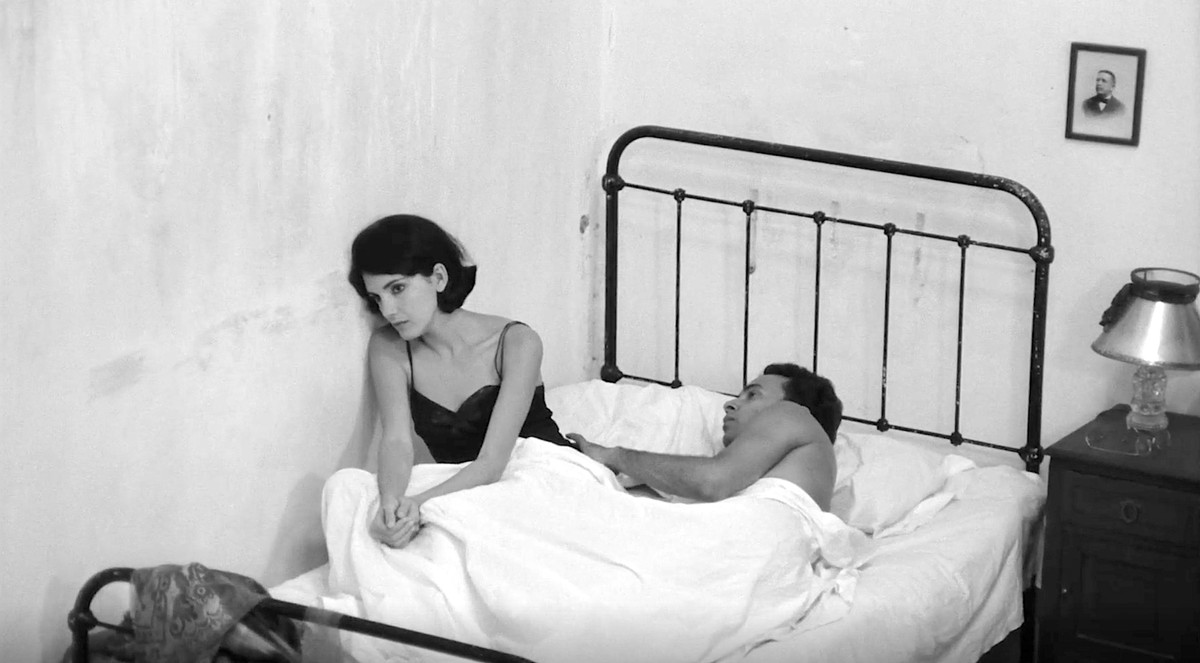

Trois destins de femmes cubaines au prénom identique, à trois périodes historiques distinctes, ou l'évolution de la condition féminine dans la plus grande île des Antilles. La première Lucía, issue d'une famille de la bourgeoisie coloniale, s'éprend d'un bel Espagnol déjà marié dans son pays. En découvrant cette réalité, elle en perd la raison. Nous sommes au moment de la guerre d'indépendance contre l'Espagne (1895). La deuxième Lucía (cette fois de classe moyenne) s'engage aux côtés d'un révolutionnaire dans le combat contre la dictature de Gerardo Machado (1932). Dernière partie du triptyque : durant les premières années de la Révolution cubaine, Lucía est cette fois-ci une ouvrière agricole souffrant du machisme de son conjoint dans une société socialiste défendant officiellement l'égalité des sexes.

Festivals & prix

Fiche technique

Voulez-vous montrer ce film?

Merci de remplir ce formulaire.

Merci de nous contacter

Revue de presse

«One of the abilities of cinema is to portray what a country is going through... it is about putting the country’s face on the screen, but it’s also about enlarging one’s vision of that specific place.» Walter Salles

«ICAIC was born out of the victory of the Revolution. Those of us who were about to attempt to found a national film industry from scratch faced a set of problems that we had to resolve immediately. Our problem was a basic cultural dichotomy, as in Lenin’s thesis on national cultures. We had an elitist cultural tradition that represented the interests of the dominant class, and a more clandestine culture that had already received wide exposure; however, at some point, all artistic expression started to be converted into products of a consumer-oriented culture.

Because the elitist and the popular were so intimately tied, because petit bourgeois consciousness and influences from Europe and North America were so dominant, our general cultural panorama at the time of the Revolution was in fact a pretty desolate one. This was during the sixties, when the most important film movement was the French New Wave. Films like Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima mon amour (1959) or Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’Avventura (1960) marked most of the subsequent decade. These influences alienated us from our indigenous cultural forms and from a more serious search for a kind of cultural expression consistent with national life and with the explosive dynamism of the Revolution. Yet this was a path we clearly had to travel. Anyone who picks up the tools of artistic activity for the first time is going to be vulnerable to outside influences.

With Lucía, I wanted to view our history in phases, to show how apparent frustrations and setbacks –such as the decade of the ’30s–led us to a higher stage of national life. Whenever you make a historical film, whether it’s set two decades or two centuries ago, you are referring to the present.

Lucía is not a film about women, it’s a film about society. But within society, I chose the most vulnerable character, the one who is more transcendentally affected at any given moment by contradictions and change.»

Humberto Solás

NOTES ON THE RESTORATION:

Restored by Cineteca di Bologna at L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory in association with Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cinematográficos (ICAIC). Restoration funded by Turner Classic Movies and The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project.

The restoration of Lucía was made possible through the use of the original camera and sound negative and a third generation dupe negative provided by and preserved at the ICAIC. The state of conservation of the negative was critical, due to advanced vinegar syndrome causing portions of the film stock to colliquate (melt) or stick together; the negative also appeared heavily warped and buckled, causing the image to lose focus throughout the film. Despite undergoing several weeks of drying and softening treatments, large portions of 8 (out of 18) reels could not be used. These sections were replaced with a second generation duplicate preserved by the Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv since the film had been distributed in East Germany in the late 1960s. All the elements were wet-scanned at a 4K resolution to eliminate or reduce heavy scratches and halos. Additional documentation was used to confirm that the film had been shot on two different film stocks–Orwo and Ilford–and graded according to the time-period depicted in the film. A previously unscreened vintage print preserved at the BFI National Archive was used as a reference. The original soundtrack was in fairly good condition, with the exception of uneven and inconsistent background noise detected in the mix which required careful dynamic noise reduction.